Available numbers don’t survive ordeal by Excel

Informed Sources

Last year there was an enjoyable ongoing debate in our correspondence columns (June-October issues). In the red corner David Holmes, asking why the classic-compatible trains for HS2, now renamed ‘Conventional Compatible’, should not tilt to maximise time savings on the northern section of the West Coast main line (WCML). In the blue corner, complete with tables, former HS2 Operations Planning Manager Jeff Hawken, who argued that tilt adds weight, complexity and cuts maximum speed – and that the benefits to Anglo-Scottish timings between Preston and Glasgow should not be allowed to determine the design of the whole HS2 fleet.

This is just the sort of well-informed discussion you expect from Modern Railways readers. And it came on the cusp of a change in HS2 rolling stock policy.

When he was Transport Secretary Patrick McLoughlin emphasised that ‘HS2 will not be a separate, standalone railway. It will be a key part of our national rail network, and wider transport infrastructure’. Well, you could have fooled me.

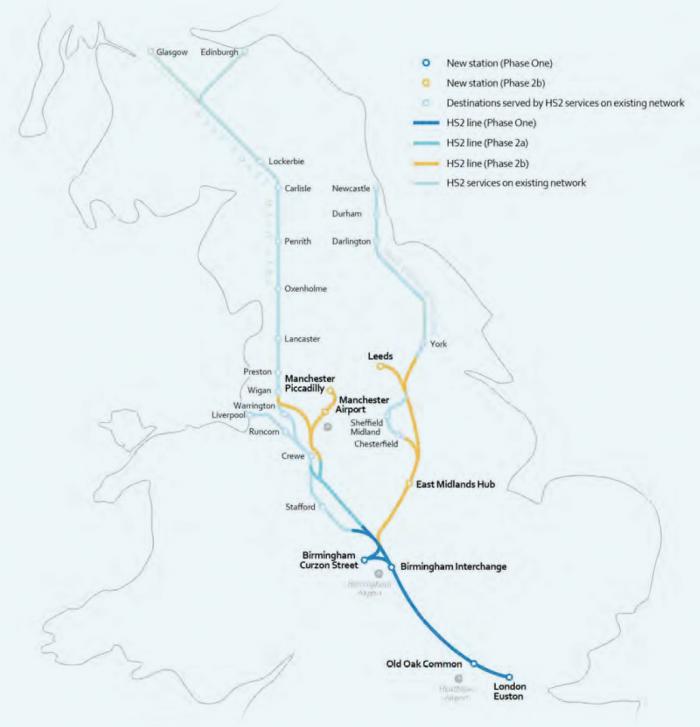

But the aspiration was confirmed by two events. First, the decision that all the initial fleet of ‘up to 60’ Very High Speed Trains (VHST) would now be Conventional Compatible sets capable of running on Network Rail infrastructure. Second, the creation of the West Coast Partnership (WCP) to run Inter-city West Coast and HS2 services as an integrated business.

FREED

Initially, a mixed fleet of 16 ‘Captive’ VHST sets, built to the maximum loading gauge, plus 45 Conventional Compatible trains, had been envisaged for HS2 Phase 1 (London to Birmingham). I was convinced that political imperatives would require Captive sets to be available for the opening of HS2 in 2026, if only to show Johnny Foreigner that the nation that gave railways to the world can still hack it (Do I need to set that in ironic bold type? –Ed).

That three-quarters of that original fleet would be Conventional Compatible sets spoke of significant mileage beyond the high-speed line. HS2’s latest number is that when Phases 1 and 2a (Euston-Crewe with a link to the WCML at Handsacre Junction between Lichfield and Rugeley) are open, 70% of high-speed services from Euston will use the national network to reach Stafford, Liverpool, Manchester, Preston, Glasgow and other destinations.

So, time to explore those journey times beyond HS2, and specifically London to Glasgow. And to avoid typing Conventional Compatible all the time, I’ll adopt the convention of calling them CCVHST.

TILT PHOBIA

Back in 2012, HS2 Ltd noted that the performance of the CCVHST on the WCML versus the tilting Pendolino was ‘more challenging’ to address because, according to un-named ‘train manufacturers’, a tilting CCVHST was not then considered ‘reasonably practical in weight, complexity and cost terms’. HS2 estimated that the absence of tilt would cost 11 minutes on London-Glasgow timings.

To reduce this disadvantage, HS2 said it had been working with Network Rail to identify a number of ‘limited adjustments’ to the WCML infrastructure that ‘with appropriate speed signage’ would reduce the differential to four minutes. Now, as far as I know, those ‘limited adjustments’ have not been published.

There are certainly time savings to be made north of Crewe, but they will not come cheap. And, of course, if the conventional linespeed is raised, a Class 390 would still be able to run faster. Or so you might think.

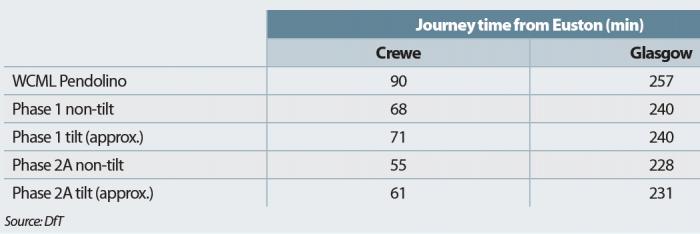

TABLE 1: ANGLO-SCOTTISH JOURNEY TIMES

BULL

To put what follows in context we need a slight digression. In 2005 the philosopher Harry G. Frankfurt published an essay entitled ‘On bullshit’, exploring the rise of this phenomenon in communications. In particular, it drew the distinction between lies and bullshit.

A lie implies recognition of the truth. Bullshit, in contrast, has no relationship with the truth at all. In current terms you could describe it as alternative truth. The claims for Inter-city Express Programme bi-mode performance were a classic example.

So, with this in mind, let’s turn to a lively battle between the railway Lord, Tony Berkeley, and the Department for Transport on HS2 journey times. In February this year he asked for the expected journey time differences between London and Crewe and Glasgow from 2027, when Phases 1 and 2a are completed, compared with the present Pendolino services. As a supplementary he asked whether HS2 had estimated the time saving were the HS2 trains to incorporate a tilting mechanism.

Replying, the Lords transport spokesman Lord Ahmed said that while the HS2 rolling stock tender specification would not preclude a bidder offering a tilting train solution, no tilting trains currently operate faster than 250km/h. That said, HS2 Ltd assumes that tilting rolling stock could achieve a maximum operating speed on the new line of 300km/h rather than the 360km/h specified for non-tilting CCVHST.

Lord Ahmed helpfully added that, in addition to increasing journey times on the HS2 infrastructure, the tilting train’s lower speed could also reduce network capacity. Meanwhile, HS2 Ltd has assumed a number of ‘minor linespeed improvements’ on the northern WCML for non-tilting rolling stock.

Table 1 accompanied the answer. I’m not sure where that 4hr 17min Euston-Glasgow time comes from, as the current schedule is 4hr 31min with six stops. The HS2 Phase 2a time of 3hr 48min correlates with the CCVHST pre-qualification technical specification, which requires a journey time of less than 3hr 45min 30sec, including stops at Old Oak Common and Preston with two-minute dwell times. I’m sure Professor Frankfurt would appreciate the faux precision of that 30 seconds.

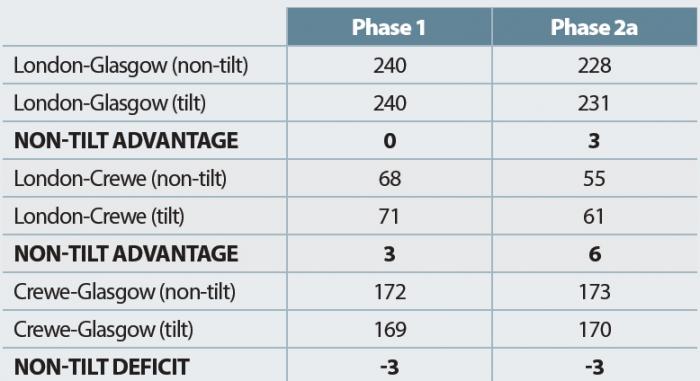

Table 2 uses the data in Table 1 to show where time is lost and gained. Remember this is comparing a tilting train limited to 300km/h on HS2 with a 360km/h CCVHST.

TABLE 2: TIMINGS WITH TILT

What this implies is that over the 191km from Euston to the WCML at Handsacre Junction, the extra 60km/h is worth three minutes. Then, north of Crewe, tilt pulls back three minutes.

Back came the indefatigable Berkeley. Does the 4hr 17min journey time for the Pendolino to Glasgow include the benefit of the ‘minor linespeed improvements’ on the northern WCML included for the four-hour journey time quoted for Phase 1 non-tilt, he wondered?

Well, no, because, according to DfT, the WCML has been optimised for tilting trains running at 125mph, while non-tilting trains are limited to a maximum of 110mph. However, north of the future Bamfurlong Junction, where HS2 will join with the WCML south of Wigan, ‘track geometry on some sections of line may allow non-tilting passenger trains to operate up to 125mph within the existing operational rules and without track changes’.

Enlarging on the improvements, DfT explained that ‘minor infrastructure alterations’ could be made on the transitions between straight and curved sections of track to optimise the speed profile for non-tilting trains, which would make no change to the speed profile of existing tilting trains. The journey time differential between a tilting train and non-tilting train would therefore be reduced.

HS2 map showing construction phases.

360KM/H FANTASY?

Informed sources suggest that, given the funding (which we do not have), you could take out perhaps 10 minutes for tilting trains between Crewe and Glasgow. But unless all easements allowed the conventional train to run at 125mph, the tilting train would gain more. However, the real point to emerge from the tables concerns HS2 linespeed. Here is Lord Berkeley probing a different issue: ‘What estimate has been made of the percentage reduction in capital and operating cost of HS2 if the maximum operating speed were 320km/h rather than 360km/h?’.

Back to Lord Ahmed again. ‘The Government believes that HS2 should be designed to a maximum speed of 360km/h, with a route alignment enabling up to 400km/h in the future. While a lower operating speed – including 320km/h – could result in marginally reduced rolling stock capital costs and some reduction to operating costs, these are more than offset by the significant loss in revenue and user benefits’. Note that ‘significant’.

Back to Table 2 and replace ‘Non-tilt’ with 360km/h and ‘tilt’ with 300km/h. And what do we notice? A difference of just six minutes when Phase 2a to Crewe is completed.

So at 320km/h we might suggest five minutes’ difference on a London-Crewe journey time of 60 minutes. Now that’s 8%, which, depending on elasticity of journey time, could indeed represent a significant amount of revenue foregone. But I suspect that in their Trumpian desire to have the ‘Greatest railway in the world. Very fast’, HS2 and DfT are in denial about the cost of 360km/h.

REAL WORLD

In a recent article in Railway Gazette International, that doyen of high-speed rail reporting, Murray Hughes, noted that although French Railways’ Ligne à Grande Vitesse Sud Europe Atlantique (LGV SEA) has a design speed of 350km/h, trains will run at 320km/h. SNCF told Mr Hughes that its customers would not wish to travel at the higher speed because ‘it would raise fares sharply for a marginal gain in time, everything from maintenance to energy costs would have risen exponentially, which simply wasn’t worth it’.

I passed this on to Lord B who put it to DfT. In a classic of governmental weapons-grade hubris the reply was ‘HS2 Ltd has collaborated with several high-speed rail Infrastructure Managers, including SNCF, to ascertain the implications of running trains at 360km/h. Using recommendations based on experiences of managing High Speed Lines in Europe, HS2 Ltd intends to incorporate specific components in the track design which will improve the system performance while utilising an Infrastructure Management System that determines asset performance and condition at all times. The combination of these factors and the use of innovative maintenance activities, that go beyond current best practice, should reduce the maintenance implications of running at these speeds’.

WORLD LEADERS

Ah, yes, good old ‘innovation’, the last refuge of a bullshitter. So HS2 is going to show SNCF how high-speed infrastructure should be built and maintained. But notice, no rebuttal of the increase in energy costs.

And it’s not just the French sticking at 320km/h. Fellow writer David Haydock asked me a technical question about ballasted track in the context of Italian high-speed infrastructure trials, which ended in November 2016. The aim of the tests was to investigate the feasibility of authorising that triumph of Japanese high-speed technology, the ETR400, to run at up to 350km/h in commercial service.

A new Italian record of 394km/h was achieved in the process. But while this work showed 350km/h to be technically feasible, the cost to the infrastructure was considered uneconomic so the linespeed uplift was limited to… 320km/h.

Even the Chinese, who, in December 2009, began running trains on the 922km Wuhan and Guangzhou route at 350km/h, have subsequently toned down linespeeds to reduce energy consumption and operating costs. My international chum Chris Jackson of Railway Gazette, fresh from a recent visit, tells me that 305-310 km/h is the current speed.

WHY 360?

So why the insistence on 360km/h running on HS2? Here’s DfT’s explanation. ‘Reducing the maximum speed of trains from 360km/h to 320km/h would result in trains taking longer to complete their overall journey. This means that, unless we buy more train sets, we will not able to run as many train services on HS2 and therefore capacity will be reduced’.

But as Table 2 shows, the time differential between 300km/h and 360km/h is low single-figure minutes. When you work up a notional rolling stock plan based on, say, 30-minute turnrounds and clockface departures, three minutes’ difference does not allow the faster train to occupy an earlier departure, which is needed to reduce the number of diagrams.

SPEED FREAKS

So 360km/h is a shibboleth rather than a rational technical and commercial choice. That it is a Frankfurt number (A frankfurter? Ed) is confirmed by the pre-qualification technical summary for the new fleet, which notes that the anticipated maximum speed (360km/h) exceeds the technical scope of the relevant locomotives and passenger rolling stock (LOC&PAS) Technical Specification for Interoperability, which is 350km/h.

In other words, TSI-compliant equipment will not meet the HS2 specification. At contract negotiations I reckon the engineer:lawyer ratio will be 1:2.73 (Is this a Frankfurt moment? Ed).

Bearing in mind the first order will be for CCVHST sets, putting the traction power needed for 360km/h into the national network loading gauge is going to be a mite difficult. Resistance to be overcome increases with the square of the speed. Running at 360km/h rather than 300km/h increases power consumption of a 200m-long train by around 3 MegaWatts, or 70%. A back of the envelope estimate puts the cost of the extra electricity at around £50 per hour per train.

So it looks to me as if, with the new HS2 rolling stock, we are back in the early days of IEP specification and procurement. Worrying. And more next month, with a detailed analysis of that pre-qualification technical specification.