Early termination gets everyone off the hook, and not just Stagecoach

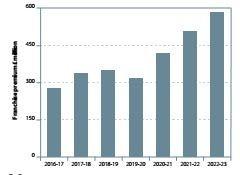

As a writer I don’t like the claim that a picture is worth a thousand words, but Figure 1 is an instant reminder of how Stagecoach got into trouble so quickly with its Virgin Trains East Coast franchise. Traditionally franchise premium profiles have saved the biggest payments until the later years. This ‘back-end loading’ inflates the Net Present Value of a bid while, if the worst happens, it at least puts off the day of reckoning.

Of course, until the Inter-city West Coast fiasco forced a radical reappraisal, transport groups basing bids on estimates of ridership and revenue anything up to 10 years in the future had the protection of the DfT’s cap & collar scheme. Typically becoming available after four years, this scheme provided support on a sliding scale if real world revenue fell below that forecast in the franchise bid, capping the loss.

If business was better than expected, DfT collared some of the extra takings. Current franchise agreements limit the franchisee’s exposure to revenue risk through the Forecast Revenue Mechanism (FRM). In the case of South Eastern this will come into effect from 1 April 2020.

RE-PRIORITISED

But while the VTEC premium profile was back-end loaded, it is also front-end loaded. Couple this with a softening of the market and Stagecoach – which owns 90% of VTEC – was soon having to top up the franchise’s premium payments.

Back in the August issue this column analysed the situation, which is not as simple as the Branson bashers, bring back British Rail proponents and left wing politicians would like to believe. As Stagecoach pointed out when it broke the bad news to its shareholders, ‘the scope and timing’ of the delivery of the new rolling stock under the government’s Inter-city Express Programme and Government-owned Network Rail’s ‘reprioritised’ infrastructure upgrade programme for the East Coast main line were ‘not consistent with what was assumed in our franchise bid and then contracted’. Table 2 shows what VTEC was expecting on the rolling stock front.

Following the delay to the GWR acceptance programme waiting for the electrified test section to become available, the official delay is currently 90 days. Meanwhile there could be further acceptance issues to be resolved on the East Coast infrastructure, notably twin pantograph operation. As we also know, it may be necessary to keep a stud of IC125s for the hourly 4hr London to Edinburgh services until the traction power supply north of Doncaster can be beefed up.

INFRASTRUCTURE

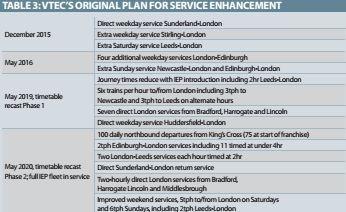

But rolling stock delivery issues are the least of DfT’s worries when it comes to VTEC. Table 3 shows what Stagecoach was expecting to drive that classic straight-line premium growth from 2019-20 to the end of the franchise.

Since DfT is responsible for both the IEP contract and nationalised Network Rail, it was on the hook as much as, if not more than, Stagecoach. Indeed, we have a variation on the Stockholm syndrome where captives identify with their captors. Apart from VTEC, DfT is also in the middle of heavy renegotiations on new Direct Award contracts for Virgin Trains West Coast and also East Midlands Trains (Stagecoach), where the franchise has already been extended to March 2019 with the prospect of a further Direct Award. Note that Direct Awards are not extensions to the existing franchise but an entirely new agreement, hence the protracted negotiations.

FIG 1: VIRGIN TRAINS EAST COAST PREMIUM PROFILE

TABLE 2: INTER-CITY EAST COAST IEP DELIVERY SCHEDULE

RE-BOOT

So despite VTEC losing money, Stagecoach, with a £3.6 billion turnover, can afford to absorb the losses until der tag when the 2019 timetable doesn’t happen and the subsequent impact on the revenue forecast is all DfT’s fault. In July Stagecoach said it had made provision for losses at VTEC of £84.1 million over the next two years (2017-18 and 2018-19), in addition to drawing down £57 million from Stagecoach’s £148.5 million 90% share of the parent company support loan commitment in the franchise agreement.

Thus the pressure was on DfT to find a way to justify pressing ctrl-alt-del and rebooting a ‘clean’ Inter-city East Coast. And on 29 November 2017 Transport Secretary Chris Grayling revealed the cunning plan in the form of the East Coast main line becoming ‘the first of the new generation of long-term regional partnerships which will be introduced from 2020’.

The East Coast Partnership, between the public sector and a private partner, will be operated by ‘a single management, under a single brand and overseen by a single leader’. It will be responsible for both inter-city trains and track operations, will be set up over the next two years and will be ‘responsible for the lines between London, Yorkshire, the North East and Scotland’. The private partner ‘will have a leading role in defining future plans for route infrastructure’. Government will work with the Office of Rail & Road, Network Rail, and all operators ‘to ensure that none are disadvantaged by the new model’.

ORR will continue to ensure that robust protection for freight and other passenger operators is maintained. With masterly understatement, DfT cautions that moving to this model ‘will require changes in the way both the train operator and Network Rail are organised and work together in order to better align their incentives’. A route supervisory board will provide a forum for passenger operators on the route to have a voice.

FIG LEAF

There are two factors that confirm that the East Coast Partnership is a double-sided fig leaf aimed at covering both DfT’s backside while protecting Stagecoach’s private interests. First, the inter-city company is a minority operator on the route in terms of trains per day. The tail will be wagging the dog and it is hard to think of a worse route on which to pilot a new, barely defined concept. Second, the ‘from 2020’ timescale allows a ridiculously short time to create the framework of the entirely new Partnership, let alone put the concept out to tender, submit bids, evaluate bids and then mobilise. And who knows what state the ECML capacity upgrade programme will have reached by 2019 when the bidding would have to start? Which leaves DfT currently in discussions with Stagecoach-Virgin, ‘to ensure the needs of passengers and taxpayers are being in met in the short term while laying the foundations to bring forward the reforms in full under a long-term competitively procured contract’. According to a DfT chum we need to read the words of the statement carefully, which is why they are quoted verbatim.

Speaking at the announcement of the Group’s latest interim results in December, Stagecoach Chief Executive Martin Griffiths was ‘encouraged’ by the Government’s positive new direction for Britain’s railway’. He added that the strategy was ‘a clear statement of intent to seek to negotiate new terms for the East Coast franchise with VTEC’. With the discussions making good progress ‘we are hopeful of reaching an agreement through to 2020 within the next few months’.

Just to round things off, time for a quick look at that ‘from 2020’ timescale for the start of the new Partnership. Assume that Mr Griffiths’ ‘next few months’ means that VTEC 2.0 comes into effect on 1 April 2019. It is then going to take at least two, probably three, years to sort out/ rescue the Inter-city East Coast timetable, especially power supply and rolling stock issues. Given DfT’s past prudence I would expect the April 2019 deal to be a two-year management contract with an optional extension of at least another two years. That takes us up to 2023, by which time the start of Control Period 7 is only a year away.

With the crystal ball in over-the-time-horizon mode, Old Ford’s almanac predicts that if it ever happens, bidding for the East Coast Partnership will start early in 2023 with the new management taking over on 1 April 2024.

MAYNARD’S FIG LEAF

Andy McDonald (Middlesbrough): To ask the Secretary of State for Transport, in light of his announcement to truncate the East Coast Main Line franchise and change to a Public Private Partnership operation, (a) for how long he expects Virgin Trains East Coast to continue to pay premiums under the remainder of the truncated franchise arrangement and (b) what estimate he has made of the value of those premium payments in each remaining year of that arrangement.

Paul Maynard (Blackpool North and Cleveleys): We have set out our plans to end the operational divide between track and train, and from 2020 we intend to establish the East Coast Partnership, one of the first of a new generation of integrated regional rail operations. We intend to identify the private partner via a competitive process, and will include appropriate contributions paid from the partner to the government.

ANDREW ADONIS REDUX

@Andrew_Adonis

REAL RAIL STORY TODAY: HMG is bailing out Stagecoach/Virgin on East Coast because they overbid. Franchise was due to end in 2023. HMG has now, incredibly, agreed to replace it by a ‘public private partnership’ (!) in 2020. They shd have kept my public East Coast company in place

@Andrew_Adonis

2/ DfT has serious questions to answer about the fiasco on East Coast & why they are (in effect) bailing out Stagecoach/Virgin with taxpayer money. National Express asked me for a bail out on East Coast in 2009. I refused & nationalised the franchise rather than do so.

No, it’s a bit more complex than it was in your time, Andrew. Do keep up.

TABLE 3: VTEC’S ORIGINAL PLAN FOR SERVICE ENHANCEMENT